We're about to dive into the fascinating world of attachment styles and how you can move closer to that holy grail of relationship happiness: secure attachment.

Attachment theory, developed by psychologist John Bowlby, provides insights into how our early relationships with caregivers shape our emotional and relational patterns throughout life. Today, however, we know that attachment styles in adulthood are influenced by a variety of factors, one of which is the way our caregivers cared for us, but other factors, including life experiences, also come into play.

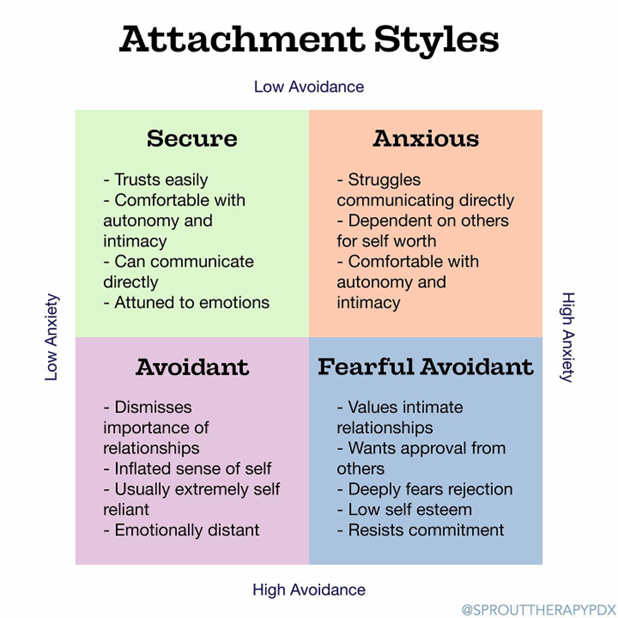

Attachment styles are the different ways individuals form and maintain emotional bonds with others.

Understanding Attachment Styles

1. Secure Attachment:

People with secure attachment styles are comfortable with emotional intimacy and autonomy.

They trust their partners, are comfortable expressing their feelings, and effectively communicate their needs.

Securely attached individuals have a positive self-esteem and a positive view of others.

2. Anxious Attachment:

Individuals with this style often fear rejection and abandonment.

They tend to be overly dependent on their partners and may exhibit jealousy,

neediness, and insecurity.

Communication can be intense, with a constant need for reassurance.

3. Dismissive- Avoidant Attachment:

People with this style value independence and self-sufficiency.

They are uncomfortable with emotional intimacy and may downplay their feelings or

avoid emotional conversations.

Often, they demonstrate an inflated focus on self-reliance.

4. Fearful-Avoidant Attachment:

Also known as disorganised attachment, individuals with this style experience a constant tug-of-war between desiring closeness and fearing it.

They may have a history of trauma or inconsistent caregiving, leading to ambivalence about relationships.

Adapting to Secure Attachment

Now, how do you get from your current attachment style to the more coveted "secure" status? Here are some down-to-earth tips:

1. Self-Awareness:

Recognise your attachment style through introspection and self-reflection.

Understand how your attachment style has influenced your past relationships and behaviours.

2. Seek Therapy:

Consider working with a psychologist to delve deeper into your attachment style and its origins.

Therapy can help you address any unresolved issues or trauma that may be contributing to your attachment style.

3. Communication Skills:

Practice open and honest communication with your partner.

Share your thoughts, feelings, and needs while also actively listening to your partner.

4. Emotional Regulation:

Learn to manage your emotions and anxiety, especially if you have an anxious attachment style.

Mindfulness, meditation, and deep breathing exercises can be helpful.

5. Boundaries Matter:

Set healthy boundaries in your relationships.

Make sure you're not giving up your own needs and independence while respecting your partner's space too.

6. Secure Role Models:

Surround yourself with people who have secure attachment styles.

Observing their behaviour and seeking their support can be beneficial.

7. Patience Is Key: Remember, Rome wasn't built in a day, and neither is a secure attachment style. Be patient with yourself as you evolve and grow.

In the book, Attached, by Amir Levine and Rachel Heller, the principles highlighted for finding the right partner- the secure way- are used instinctively by people with a secure attachment style. They include:

Spotting “red flags” very early on and treating them as deal brakers.

Assertively communicating your needs from day one.

Supporting the belief that there are many (yes, many!) possible partners who could make you happy.

Never taking the blame for a date’s unpleasant behaviour. When a partner or date behaves thoughtlessly or hurtfully, secures recognise that it says a lot about the other person rather about themselves.

Expecting to be treated with respect, dignity and love.

In a nutshell, attachment styles can have a profound impact on our relationships and emotional well-being. While adapting from an insecure to a secure attachment style may require effort and self-awareness, it is possible with time and commitment. By understanding your attachment style and taking steps to develop a more secure one, you can foster healthier and more fulfilling relationships. Remember that seeking professional guidance and support can be invaluable on this journey towards secure attachment.

Amanda Murray, Psychologist